History makers

Hundreds of thousands have worked in the industry and today the South West’s aerospace industry employs over 43,000 people in upwards of 700 companies. Despite this, their contribution to the region’s industrial heritage has no focal point. Aerospace Bristol, located at the very heart of the industry and community, will provide unparalleled public access to information and learning about the important contribution the people of the South West have made, and continue to make, to advances in engineering, technology and global communications.

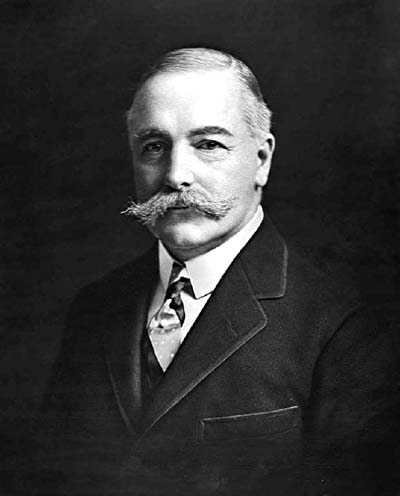

Sir George White (1854 - 1916)

It is thanks to Sir George White that the aviation industry in Bristol exists at all. George White was born in Cotham in Bristol in 1854. At the age of 15 he became a junior clerk with a firm of solicitors in Corn Street, Bristol, and was soon dealing with local bankruptcy cases. This gave him a great insight into how to run (or not to run) a business. He was made Company Secretary of the Bristol Tramway Company when it was formed in 1874, and also formed his own stock brokerage firm. In 1895, he was responsible for the first regulated electric tram service in Britain, which ran from Old Market to Kingswood. His business interests soon extended to trains, omnibuses, charabancs, taxi cabs and lorries. A keen philanthropist, for the Bristol Royal Infirmary in particular, he was made a baronet in 1904.

During a visit to France in 1909, he met several of the aviators of the day, including Wilbur Wright. With White's experience of the transport business, he could see the potential of an aeroplane factory in his home city. In February 1910 he, his brother and his son formed the British & Colonial Aeroplane Company, and set up a production line in two bus sheds in Filton. This was at a time when aviation was in its infancy, and the only other aeroplane factories in Britain were run by aviators, not businessmen. The two British aeroplane factories before British & Colonial were the Short Brothers and Handley Page, which had initial investments of £600 and £500 respectively. The start-up capital in British & Colonial was £25,000.

Within a few months, the factory was building the Bristol biplane, later nicknamed the Boxkite, and by the end of the year Boxkites were being sent on sales missions to Australia and India. Sir George continued to expand the business, by injecting more capital, taking on new designers to build more aircraft, and setting up two flying schools: one near Stonehenge and one at Brooklands in Surrey. In 1912, the capital in the company had grown to £100,000, and by 1914 around 200 aircraft had been built. By the start of the First World War, the company was a prime supplier of military aircraft around the globe.

In the early years of the First World War, Sir George White oversaw the production of the Scout biplane, which was making a name for itself over the battlefields and defending British shores. Later in the war the company built the Bristol Fighter, arguably the best British fighter aircraft of the war. Sadly, Sir George did not witness its success, as he passed away in November 1916, and the prototype had flown only two months previous.

Sir G. Stanley White 2nd Bt. (1882-1964)

(George) Stanley White was the only son of the Bristol entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sir George White 1st Bt. (1854-1916). He was educated at Clifton College. From an early age he was caught up in the vortex of his father's business interests, beginning as an authorized clerk in George White & Co., his father's Bristol stockbroking company. He became a partner in 1907. He soon rose to become a director of his father's other companies including the Bristol Tramway and Carriage Company, Imperial Tramways, the Main Colliery and the Western Wagon and Property Company.

As a young man Stanley White had exhibited a passion for speed and adventure. He was a fearless horseman and drove a sporting “four-in-hand” horse-drawn carriage with verve. When motor vehicles became practical he took up motoring with enthusiasm. He drove his first car, a French Panhard from Paris to Bristol in 1903.

When his father set out to pioneer an aircraft industry in Great Britain in 1908, Stanley White was intimately involved. He became a founding director of the British & Colonial Aeroplane Company in 1910. Although his father forbade him to take up flying himself, he was determinedly “hands on” both in the air and on the ground. He frequently flew with the pioneering French pilots they employed, especially Jullerot, Tétard and Tabuteau. He took many dramatic photographs from the air to demonstrate the vulnerability of military establishments. He published the first pilots’ logbooks for heavier than air machines. The flying schools which he set up with his father at Larkhill and at Brooklands ultimately provided two thirds of the pilots available at the outbreak of war in 1914.

In 1911 Stanley White was appointed Managing Director of the British and Colonial - later to become the Bristol Aeroplane Company - a post he held for over forty years. He had the heavy responsibility of directing the company through two world wars, building the workforce from a few hundred employees to over seventy thousand. His greatest skill was undoubtedly in providing the circumstances in which his great engineers and designers could flourish. Given that he was brought up as a businessman, Sir Stanley regularly surprised his employees by his knowledge of technical engineering.

Given that the production of all Bristol aircraft and engines built over nearly fifty years was ultimately his responsibility, one might ask why Sir Stanley White is not more famous. The answer is simply that he was a modest man, who unlike his aeronautical contemporaries, shunned publicity of all kinds. He retired as Managing Director in his seventy-third year, content to accept the office of Deputy Chairman. He continued to work at Filton every day into his mid-eighties, taking particular interest in the welfare of his employees. He died in December 1964, the Grand Old Man of West Country Aviation.

Captain Frank Sowter Barnwell (1880 - 1938)

Frank Barnwell was born in London, but grew up in Scotland. During his apprenticeship with a shipbuilder in Govan, he spent the winter months getting a degree in Naval Architecture at Glasgow University. After a year in the USA, he joined his brother Harold in business in the Grampian Engineering and Motor Company in Stirling. Between 1908 and 1910 the brothers built three experimental aeroplanes, the third of which earned them a £50 prize from the Scottish Aeronautical Society.

Frank briefly returned to shipbuilding, but Harold moved south and got his pilot's certificate in 1912, with the Bristol Flying School at Brooklands. Frank soon moved south as well, joining the British & Colonial Aeroplane Company at Filton as a draughtsman in March 1911. His first post was in the 'X Department', a secret department working on a seaplane with hydrofoils. This project was abandoned at the outbreak of war in 1914, and Barnwell joined the main office as a designer. His first project was a simple tractor biplane, named the 'Baby Biplane', which achieved 95 mph in its first test flights. With a few modifications, it was put into production, and named the Bristol Scout. It was ordered by the War Office and the Admiralty, and proved very popular with pilots.

Early in the First World War, production at Filton was given over to the Royal Aircraft Factory-designed BE.2 at the government's insistence. With no need for a designer, Barnwell joined the Royal Flying Corps, flying with No. 12 Squadron. The BE.2 proved to be inadequate, and Barnwell returned to Filton on indefinite leave from the RFC in August 1915. Following an upgraded version of the Scout, he started work on a two seat fight biplane, which led to arguably the best British fighter aircraft of the First World War - the Bristol Fighter. Apart from a period in Australia in the early 1920s, Barnwell designed almost every Bristol aircraft in the inter-war period.

Barnwell had a reputation as not being a very good pilot, and in fact the Bristol Aeroplane Company had banned him from flying factory aircraft. In the late 1930s, he designed and built a light aircraft as a private venture in his spare time. He was killed on 2nd August 1938, when the aircraft crashed on its second test flight. His legacy includes some of Britain's most successful aircraft: the Scout biplane, the Fighter, the Bulldog, the Blenheim, the Beaufort and the Beaufighter.

Sir Alfred Hubert Roy Fedden (1885 - 1973)

Roy Fedden was born in Stoke Bishop in Bristol on 6th June 1885. He joined the Brazil-Straker Company in Fishponds in 1907, bringing with him a car design that was put into production as the 'Shamrock'. He became the Chief Designer, and later Technical Director of the company. During the First World War, Brazil-Straker moved into aero-engine manufacture, building the liquid-cooled Hawk and Falcon engines under licence from Rolls-Royce. The licence prevented Brazil-Straker from designing their own liquid-cooled engines, so under Fedden's leadership, they developed air-cooled radial engines instead, namely the Jupiter, Mercury and Lucifer.

Brazil-Straker was taken over by Cosmos Engineering in 1918, but Cosmos went into liquidation in 1920. The aero-engine department was taken over by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, and the team move to Filton, bringing the Jupiter and Lucifer development with them. With BAC's backing the Jupiter became widely used in a variety of aircraft around the world, thanks to is unbeatable reliability.

The Jupiter was the first of many successful piston engines to be designed and built by Fedden's team, from the 32 h.p. flat-twin Cherub up to the 3,200 b.h.p. 18-cylinder Centaurus. Fedden's designs were ground-breaking, leading the way in supercharging, poppet valves and sleeve valves.

Fedden was knighted in 1942, and left the Bristol Aeroplane Company shortly afterwards. He became a government advisor, spending a lot of time in the USA on fact-finding missions. One aspect of his report covered aeronautical education, and was directly responsible for the creation of the College of Aeronautics, which became Cranfield University.

Captain Cyril Frank Uwins OBE (1896 - 1972)

Between 1919 and 1947, 'Papa Uwins' flew the first flight of 54 prototype aircraft, more than any other British test pilot. Uwins signed up with the London Irish Rifles in the early years of the First World War, and transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. He injured his neck in a crash, and recovered to continue flying, but restricted neck movement meant he became a ferry pilot and instructor. He was then assigned to the Aircraft Acceptance Park at RAF Filton, test flying locally built aircraft and ferrying them to the front line in France. He was seconded to the nearby factory in August 1918, and became chief test pilot on his demobilisation on 1st April 1919.

During his 27 years as Chief Test Pilot, he flew every new Bristol aircraft type, and also flew the aero-engine test beds. In the early 1930s, Bristol led the way in supercharged piston engines, and on one flight from Filton in 1932, Cyril Uwins set a new world altitude record of 43,976 feet. This was made possible using a Bristol Pegasus engine with a supercharger, fitted to an open cockpit Vickers Vespa biplane. Uwins made some frightening first flights, such as aileron reversal in the 1927 Bagshot, however his closest brush with death was on a routine test flight in a Bristol Bulldog. An incorrectly fitted oxygen mask caused him to pass out at 27,000 feet, only coming to when the Bulldog has fallen to 18,000 feet. Without realising he been unconscious, he proceeded to climb again, and the same thing happened at 26,000 feet. At 20,000 feet he again woke, and realising something was not right, did not do any more climbs. It was only when he was back on the ground that he realised he had not connected the oxygen hose correctly.

Uwins retired from test flying in 1947, and joined the board of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, becoming Chairman of Bristol Aircraft Ltd when this was hived off as a subsidiary in 1956. He was also a director of Short Brothers & Harland and president of the Society of British Aircraft Constructors (SBAC) in 1956-57.

Raoul Hafner (1905 - 1980)

Austrian-born Raoul Hafner became interested in the theory of rotor-powered craft at a young age, and relocated his research from Vienna to the UK in the early 1930s. His early designs were gyroplanes, where the unpowered rotor acts as a rotating wing, with a conventional engine-powered propeller for thrust, as with a fixed wing aircraft.

Coming from Austria, he was interned at the start of the Second World War, but soon became a naturalised citizen. He developed some unusual craft for the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment, but he and his team joined the Bristol Aeroplane Company in 1944 when it was decided that there would be no need for rotor craft in the D-Day invasion.

The new Helicopter Division at BAC started work on the Type 171 helicopter, which made its first un-tethered flight in 1947. It was the first British helicopter to be granted a civil certificate of airworthiness, and it entered RAF service as the Sycamore in 1953. It was used extensively around the globe for search and rescue, passenger transport and ambulance, and was particularly useful in remote or hard-to-reach places.

Hafner's next project was a twin-rotor twin-engine transport helicopter, the Type 173, which flew in January 1952. This helicopter could be used to carry troops or lift heavy objects, or transport passengers to city centre locations. Although several versions were planned, only the Belvedere, a troop carrier for the RAF, made it into production. The Belvedere was named after a Baroque palace in Hafner's home city of Vienna.

Henri Marie Coanda (1886 - 1972)

Henri Coanda was the son of General Constantin Coanda, a professor of Mathematics in Bucharest, Romania. After a number of years studying engineering in Germany, Belgium and France, at the 1910 Paris Salon he unveiled a novel aeroplane powered by a ducted fan. It seems the aircraft did not fly, however he later claimed that it had, and that he was the inventor of the first jet powered aircraft.

Coanda joined the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company in January 1912 as an aircraft designer, and his first aeroplane, a two-seater monoplane for pilot training, was ready for flight the following March. In all, 13 examples of this type were built, in both side-by-side and tandem layout, including a number sent to Italy and Romania. A military version was entered in the War Office's Military Aeroplane Competition in July 1912, and although it did not win, it performed well and was acquired by the War Office anyway. The Coanda-Military proved to be very popular, especially with the Italian and Romanian Governments; however, a War Office ban on monoplanes limited their success.

In 1913 Coanda adapted his monoplane design into a biplane, named the TB8 (TB for Tractor Biplane). Fifty-four were converted from existing monoplanes or built new, including a seaplane version. The second 'new-build' TB8 was fitted with a basic bomb bay, a prismatic bombsight and release trigger, making it the world's first purpose built bomber when it was delivered to the Admiralty in March 1914. A number of TB8s were used in France to bomb enemy positions in the early months of the First World War.

Henri Coanda left the company in 1914, and later became Minister of Science in Romania. He is perhaps better known for discovering the Coanda Effect, which is where a fluid which flows close to a convex surface will be deflected, as happens when air passes over the top of an aircraft wing. The Coanda Effect can be demonstrated by holding the underside of a spoon very close to (but not touching) a stream of water from a tap.